OpenFlexure: What It Takes to get Medical Device Certification for an Open Source Microscope

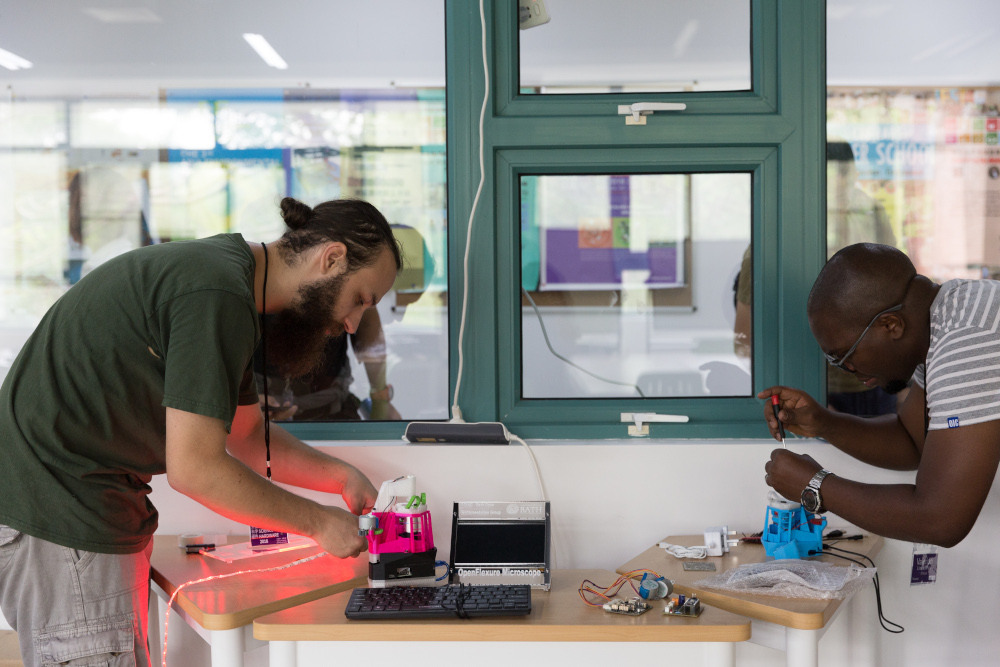

Julian Stirling (left) and Valarian Sanga, co-founder of BTech, assembling microscopes. [1]

Julian Stirling (left) and Valarian Sanga, co-founder of BTech, assembling microscopes. [1]The OpenFlexure microscope is an open hardware, laboratory-grade device that has been used to diagnose malaria and cancerous cells. Using off-the-shelf components and 3D-printed parts it can be build for around 400 euros, bringing automated digital microscopy to underserved communities.

OpenFlexure started as an academic research project in 2016 and has since been built and used in over 60 countries. Julian Stirling is one of OpenFlexure’s core developers and chief executive of Humanitarian Technology Trust. In this interview he talks about the project’s next steps: to facilitate local manufacturing, maintenance, and support with medical certification.

How did you get involved in the OpenFlexure Project and why did you think it was important?

I had a history in designing hardware for scientific instruments and was very embedded in the open source software community. In 2018 there was a job advert from Bath university to work as a Post-doctoral Research Associate on OpenFlexure. I saw this opportunity to do what I love with scientific hardware development but being able to do it open source, which is so important for reproducible science. Because that is one of my biggest frustrations in science: we're talking about making science reproducible by writing papers but we are actually hiding all of the real content. That is, if I've designed a scientific instrument and you want to reproduce it, you need to know how to reproduce it. And I thought it was important because it is a fantastic project: helping to build microscopes with the long-term goal of malaria diagnosis. It gave me an opportunity to see a different part of the world and get involved in the work that was happening in Tanzania.

An important next step for OpenFlexure is to get medical certification for the microscope. Why is that important and what is needed to realize that?

The OpenFlexure Microscope has reached the instrument performance to see parasites for malaria and to be able to identify cancer cells. At least, if it's in the hands of a skilled user. But you can't get microscopes into clinics for routine use unless they're being made at a medical grade. As we explain on our website: medical certification depends not just on the design but also the manufacturing process. Certificats can only be issued to a particular manufacturer because you need assurances that the device is assembled according to strict standards.

So on the one hand we are working on a good enough technical file to transfer the design so it can be used for medical use. And on the other we are working on capacity building with in-country manufacturers so they can get a certification for the microscope. Enabling them to sell it in-country as an in-vitro diagnostic device.

It is a long-term goal. For instance, we've been working with our partners at BTech in Tanzania. When they talked to the Tanzanian Medicines and Medical Devices Authority, it turned out the TMDA had never certified a digital in-vitro diagnostic device. Or at least not something as complicated as the microscope. So there's some capacity building with regulators as well.

We could have opted for a different route: just register a company in the UK and subcontract manufacturing out to Tanzania. The reason we want to do in-country manufacturing is that so often the problem with availability of medical devices comes down to long-term support and maintenance. If you're in an area where large companies don't have support engineers then often devices end up not working. So local manufacturing enables local repair.

We could probably speed things up by just subcontracting but we'd retain all the power. They'd be licensing everything off us. We'd do the medical paperwork and then we'd be responsible for checking that they were following our procedures. That would mean at any point we could turn off the tap and tell them to stop. And I think global history has shown that when power is concentrated in the UK it doesn't necessarily work for everybody else. So we're taking a slower approach but also fairer approach where everybody maintains ownership over what they are producing.

The OpenFlexure project has received NGI Zero funding for further development. Can you tell us what you are working on in that particular context?

The NGI Zero funded development focuses on collecting and sharing of data to facilitate remote second opinions. Second opinions are very common in the medical profession. Doctors in large medical facilities consult with their colleague across the hallway all the time. But if you are in the rural Amazon that might be significantly more problematic.

That’s why we are developing the microscope to enable remote second opinion, or, telepathology. We are not trying to outsource the entire diagnostic process away from local communities but we want to give access to this sort of ongoing communication between doctors. So we are working on tooling both around the data collection and the data sharing so doctors can simply get on a video call, bring up an image of a biopsy and discuss the diagnosis.

There’ll also be work done to make the user interface (UI) more robust. It’s creaking a little because the project is largely developed in academia. And anything you do in academia needs to be funded as research. Which means that things like keeping your UI up to date is something you have to do in the evenings and weekends.

Can you say something about the community around OpenFlexure?

Trying to build a community around a hardware project was interesting. It is much easier to get your hands on a software project because somebody can hopefully build it in a docker container. We've struggled to find a docker container that can build a whole microscope. So that means that people need to source the individual components.

For a time our single source of truth was our GitLab and we told everyone to go there. The biggest change in our community was when we created a normal forum. To me the Git issue thread is a forum but there is so much else happening that it may scare people. If you’re not a software developer you may feel this is not for you. So we’ve set up a forum and now we’ve got five or six hundred people participating.

People are involved with the microscope in different ways: there are people building it, using it, selling it, teaching it, and developing it. We always ask people who’ve built or used the microscope to tell us where they are. So far we are in 67 countries I think, and seven continents as there is someone with a microscope on the Antarctic sea ice.

More recently a vendor network has set up through something called the Open Science Shop which originally was a project of Gathering for Open Science Hardware. So now we have a manufacturing community of people selling kits. They have monthly calls and arrange shared procurement which really increased access for some of them. There are people who give workshops on how to build and use the microscope in countries like Sweden, Ghana, Scotland, Senegal and Ukraine. And then there are people developing it many of whom are in academia.

The manufacturing costs of OpenFlexure microscopes are less than 5% of its commercial counterparts. Shouldn’t all medical devices be open source?

When we talk about why things are done open source, we very quickly get into business models. For hardware you can at least say that people expect to pay money for it, whether it’s open source or not. The cost of hardware design is very high and then you have to include the medical regulatory processes. We haven't found a sustainable business model to fund that yet.

But even if the entire medical device is not open source, I think there are great arguments to be made for more openness. If new technologies are developed with public funding then it should not be patented. In the same way we talk about ‘public money, public code’ I think we should speak of ‘public money, public invention’.

But at the same time, for many people the default thinking about open hardware is: “I can make it in my garage”. And no one should be making medical hardware in their garage unless their garage is certified to ISO 13485. Not just because regulators like people jumping through hoops, but because all of these processes are very important for making sure that the device does what it should do every single time. Which is really important when human life is on the line. So it's a very complex field for manufacturers. But there's definitely a lot more openness to be had, especially when public money is put into developing technology.

Earlier this year you and others founded the Humanitarian Technology Trust and you took on the role of Chief Executive. Can you tells us about goals of this charity?

In the UK there is the Global Challenges Research Fund which provides grants for academic research related to international development. So there is all sorts of fantastic research being done and papers being published about democratizing technology X and Y. After the initial funding runs out you need to take these projects to the next phase. But universities only understand one way of commercializing or creating technology transfer which is to spin out a for-profit company. But that is not aligned with OpenFlexure’s goals. We do want local manufacturers to be able to make profit but we don't want centralized IP and us making a huge profit in the UK. Because then we end up back in the same model as everybody else and we haven't democratized technology at all.

So there is a huge need for an organization that can effectively act as the technology transfer vehicle. Because once you finish your academic project and proved a prototype can work, there is a lot of work ahead. There's all of the designs for manufacturing, there's all of the documentation. We've put thousands of hours into documentation. So we deliberately founded the Humanitarian Technology Trust and not the OpenFlexure foundation. Because while at first we only have capacity to work on OpenFlexure, it would be a shame if we can’t harness this knowledge for the next project in academia that has similar goals. So the long-term goal is to be an example of a pathway for technology transfer.

If people are interested in the OpenFlexure project and would like to participate, how can they help?

We're always looking to grow the community so people are welcome to join. The best port of call is the forum, just reach out and tell us why you're interested in the in the project. Everyone is welcome but I’ll mention a few specific things we could use help with. People who are good at packaging operating systems because trying to actually reproducibly build the operating system is a problem. If anyone knows about the libcamera software stack that would be a great help because we're moving from the old raspberry pi. We've made a lot of progress with it but there's certain bits we don't understand as well as we could. We have a JavaScript UI and I hate writing JavaScript. There are also non-technical roles we could use help with. I would love people forever if they’d come and help with the documentation, project management, or any of the community support.

The interview was conducted by Tessel Renzenbrink, communication officer at NLnet.

[1] Image: courtesy of the Gathering for Open Science Hardware project. It depicts Julian Stirling (left) and Valarian Sanga, co-founder of BTech, assembling microscopes.